Monday, November 27, 2006

CHAT SESSION WITH CHIEF JUSTICE HILARIO DAVIDE

CHAT SESSION WITH CHIEF JUSTICE HILARIO DAVIDE: "Chat Session with Chief Justice Hilario Davide"

Labels:

PVCHR post in other than Hindi

Why Karmeena Musahar died

Why Karmeena Musahar died

By Anosh Malekar

Five children have died of hunger-related causes in the Musahar community of eastern UP since May 2006. Entire families in this and other communities in the state are starving. In addition to extreme poverty, the Musahars’ low status in the caste hierarchy keeps them out of government food and employment schemes. As India claims to join the league of globalised nations, it cannot ignore these everyday realities of millions of its citizens.

All was quiet when we reached the village. There was no visible sign of the death that had occurred the previous night. It was not the first time the predominantly upper-caste Thakur-Brahmin village of 6,000 people was witnessing a death in the tiny settlement of Musahars, a community that has unfortunately become known as the “rat-eaters”.

Belwa is about 25 km from Varanasi in eastern Uttar Pradesh, on a flat land of mango groves and rice fields. The village is approached by an 8-km dust track off the Varanasi-Lucknow highway.

On August 31, 10-year-old Karmeena Musahar had come in the morning to the community centre and informal school run by a Varanasi-based NGO. That evening she ate some rice and vomited. She got a high fever and by 1 a m on September 1 she was dead. "She went peacefully,” her grandmother, Hirawati, said.

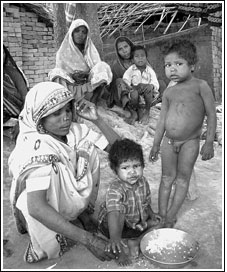

Karmeena's father Buddiraj was away with the men in the community to perform the final rites when we got there around noon. Her grieving mother Badama spoke about their impoverished existence while feeding morsels of coarse rice to her surviving sons, four-year-old Monu and two-year-old Jadu.

There was little to eat in the house for three months. Buddiraj and Badama are bonded labourers on a brick kiln, which was closed for the monsoon. They had taken an advance of Rs 1,000 from the brick kiln owner, Ramashray Singh, the previous season and were struggling to pay back the last few instalments totalling Rs 300. The family was surviving on rice, grain chaff, salt and chillies.

The pradhan (village head), Rajendra Tiwari, said this was not unusual. The Musahars have always lived in abject poverty. "They are our praja (subjects) and but for our benevolence would all have died of hunger," he said magnanimously.

Karmeena is the fifth child in Belwa to die of hunger-related causes since May 2006. Nine-month-old Seema Musahar died on July 28 after desperate attempts by her mother Laxmi to get Rs 1,000 from the Varanasi district magistrate’s emergency funds. Seema too had developed high fever and Laxmi had to pawn two old saris to get some money to treat her, which was not enough to save her.

Like most Musahar couples, Laxmi and her husband are bonded labourers at a brick kiln, drawing pitiful amounts of low-quality grain and chaff as payment. Laxmi's father Phoolchand also recently died of starvation.

The Varanasi-based People's Vigilance Committee for Human Rights (PVCHR) and the Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) have documented these deaths, along with those of Muneeb Musahar, a three-year-old boy of the same village who died on May 29, Monu Musahar, a one-year-old boy and a newborn baby girl, who died without a name.

The organisations wrote to the district and state authorities that at least 30 of the 100 Musahar families in Belwa were starving to death. Most of these families were cooking food only once a week. They had no access to foodgrain from the public distribution system or any of the government assistance programmes.

When no one responded, the PVCHR and AHRC wrote to the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) and the Planning Commission. The district administration moved only after the NHRC issued a notice seeking explanations for the hunger deaths. The Hong Kong-based AHRC wrote to the authorities in New Delhi and took the case of the starving Musahars to the United Nations (UN), the international media and other rights groups. It also demanded that the State Human Rights Commission in Uttar Pradesh conduct impartial inquiries into the starvation deaths.

Lenin Raghuvanshi of the PVCHR said the authorities are inactive and hostile because the village headman, the district magistrate and other functionaries are “caste-conscious feudalists with an interest in keeping the Musahars as social outcastes”. When the DM, Rajeev Agarwal, finally visited Belwa, he only talked to the headman.

In a statement on July 27, the AHRC and PVCHR said, "India is trying to project itself as a State looking forward to a place in the league of developed nations. It has put a claim, as a leading Asian and global power, to permanent membership in the UN Security Council. However, the true measure of development is not economic growth: it is human dignity. By that measure India is among the least developed nations in the world."

High on hunger, low on development

One out of every three malnourished children in the world lives in India. As India claims to move towards becoming a global power, it has to face the fact that 46% of its under-three children are too small for their age. India has little chance of meeting a key United Nations Millennium Development Goal that aims to halve the prevalence of underweight in pre-school children by 2015.

In ‘India: Malnutrition Report’ the World Bank observes that malnutrition in India is a concentrated phenomenon—five states and 50% of villages account for about 80% of the malnutrition cases. Half of the country’s malnourished children live in rural areas. Boys and girls from the scheduled tribes account for 56.2% of the malnourished children. Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Bihar, Orissa, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan, all with a sizeable adivasi population, account for about 43% of India’s hungry children.

The Musahar children would be among the 60 million malnourished children in India that another recent World Bank report titled ‘India's Undernourished Children: A Call for Reform and Action', speaks of. They remain hungry in spite of the world’s largest feeding programme for school children. Often the mid-day meal in school is the only meal that children like Karmeena and Seema can get to eat all day.

Although the central government-sponsored mid-day meal scheme excludes children attending non-government aided schools, the programme, launched in August 2005, was expected to provide one cooked meal of 300 calories and 8-10 grams of protein content to about 12 crore children in more than 9 lakh primary schools across India.

The Musahars are recognised as a scheduled caste (SC). They survive on the margins of villages in isolated settlements. Their traditional occupation was hunting out rats from burrows in the fields. In return they were allowed to keep the grain and chaff recovered from the rat holes. In times of drought and food scarcity, the Musahars would resort to eating rats. Many Musahar families work as bonded labourers at brick kilns.

The Musahars have mostly been denied the benefits of the government’s food security and employment guarantee schemes. When they demand their rights, as they did in Varanasi district last year, the upper castes abused them and the official machinery said they were Naxalites.

In the eastern UP districts of Varanasi, Sonbhadra, Jaunpur, Khusinagar and Mirzapur, where Musahar deaths are frequently reported, only 31% of the children under-six years are covered by the Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS), according to a study done by the PVCHR and based on the government’s own figures. At least 71 ICDS projects in addition to the existing 64 are required to cover the entire Musahar population. Some 20% of the existing anganwadi worker posts and 30% of anganwadi helper’s posts are vacant.

The PVCHR found that the five districts have utilised about 75% of the allocated funds and 56% of sanctioned foodgrains under the Sampoorna Gramin Rozgar Yojana. The National Food for Work scheme at Sonebhadra, Mirzapur and Khusinagar districts has only used 7.5% of funds and 8.6% of foodgrains so far.

The darkest of conditions

Deaths related to starvation have been reported in other very backward communities of Uttar Pradesh, like the Nuts, a community of alms-seekers, the Ghasias or grass cutters, and the Bankars or weavers. In the weavers' colony of Baghwa Nala in Varanasi, thousands of looms are lying idle because cheap Chinese yarn and silk fabric imports have deluged the Indian market. Scores of weavers who made the famous Banarasi silk saris are out of work and facing starvation.

The Human Resource Development Ministry recently underlined the need to broaden the mid-day meal scheme to include children from non-government aided schools. But state government officials often resist helping schools run by certain minority groups or allow the scheme to exclusively benefit certain caste groups. Antyodaya ration cards and cash compensations for hunger-related deaths come only after much hue and cry by human rights organisations.

The Musahars continue to be ignored in spite of the fact that parties with a backward caste base, like the Bahujan Samaj Party and the Samajwadi Party have been ruling the state in recent years. "The BSP cares only about Chamars, while the SP would not like to alienate its core constituency of other backward castes, who are the main exploiters of the Musahars," according to Raghuvanshi.

Union rural development minister Raghuvansh Pratap Singh visited Banthu village in Vaishali district of Bihar after 25 persons died of kala-azar (or ‘black fever’, a chronic and potentially fatal parasitic disease of the internal organs) in six months. Banthu has a sizeable Musahar population and is surrounded by a host of ‘VIP constituencies’ represented by Singh, Ram Vilas Paswan, George Fernandes and Rabri Dev.

"Kala-azar affects Musahars more than other communities because they are starving. The World Health Organisation has set 2015 for its eradication. But as long as the Musahars continue to face food scarcity I do not see any relief from kala-azar in north Bihar," said Reghupati (who is also Singh’s brother) of the Delhi-based Confederation of NGOs of Rural India.

Fellow activist and Bihar Panchayat Helpline convener Amar Thakur said the current kala-azar eradication programme was so devised that the impoverished Musahar had to spend nearly Rs 2,000 on tests to confirm the disease before they could become eligible for free treatment. Bihar accounts for 90% of all kala-azar cases, which affect 19 districts and close to 2 lakh people. Cases are also reported in West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Assam, Tamil Nadu and Jammu and Kashmir, where migrant labourers appear to have carried the disease, said Thakur.

About 300 Musahar families live in Banthu. In January, two brothers in their 30s died of extended starvation and kala-azar. The deaths led to protests by Reghupati and fellow activists. The district administration finally responded with Rs 25,000 cash compensation and a pucca house each for the widows, Sivanti Devi and Manju Devi, under the Indira Awaas Yojana.

The cash went into repaying old loans. There was little food to eat inside the pucca houses when we visited them in early-September. "We do not know how our children will survive the starvation after their fathers. Looking at how things have turned out for us, it is better if they never have to face such a future," the women said.

The Musahars live in dilapidated mud and straw huts surrounded by pools of stagnant water during the monsoon, which are a breeding ground for the sand fly that causes kala-azar. “People need food first before they can think of hygiene or proper housing or education,” Reghupati said. “Dealing with kala-azar means dealing with poverty and hunger. Nobody wants to do that in these times of globalisation."

The working group on elementary education in Delhi, of which the mid-day meal is a part, is preparing a strategy for the Eleventh Plan (2007-12). Perhaps it will have spared a thought for India’s 60 million hungry children before submitting its recommendations by the end of September. Otherwise, the government may have to think of more excuses for letting children starve to death.

A hungry generation

Under-nutrition, low weight, chronic illness, stunted growth—all are widespread among children in India

Inadequate or unbalanced diets and chronic illness are associated with poor nutrition among children. Almost half the number of children under three years of age (47%) are underweight. A similar number (46%) are stunted. As many as 18% of children are severely undernourished in terms of weight-for-age and 23% according to height-for-age.

Even during the first six months of life, when most babies are breastfed, 9-15% of children are undernourished according to the three indices -- ?weight-for-age, height-for-age, and? weight-for-height. At 24–35 months, when most children have been weaned from breast milk, almost one-third are severely stunted and almost one-quarter are severely underweight.

‘Wasting’ affects 16% of children under three years of age in India. The proportion of children who are undernourished increases rapidly with the child’s age through 12-23 months.

Overall, girls and boys are equally undernourished, but girls are more likely than boys to be underweight and stunted, whereas boys are more likely to be wasted. Under-nutrition generally increases with the birth order. Young children in families with six or more children are nutritionally the most disadvantaged. First births have lower than average levels of under-nutrition on almost all the measures, and children born after a short birth interval are more likely than other children to be stunted or underweight.

Under-nutrition is substantially higher in rural areas than in urban areas. Even in urban areas, more than one-third of children are underweight or stunted. Children whose mothers are illiterate are twice as likely to be undernourished as children whose mothers have completed at least high school. The differentials are greater in the case of severe under-nutrition.

The nutritional status of children is strongly related to the nutritional status of their mothers. Under-nutrition is more common for children of mothers whose height is less than 145 centimetres or whose body mass index is below 18.5.

All the measures of under-nutrition are strongly related to the standard of living. Children from households with a low standard of living are twice as likely to be undernourished as children from households with a high standard of living.

Hindu and Muslim children are equally likely to be undernourished, but Christian, Sikh and Jain children are considerably better nourished. Children from scheduled castes, scheduled tribes or other backward classes have relatively high levels of under-nutrition according to all measures. Children from scheduled tribes have the poorest nutritional status and a high prevalence of wasting (22%).

Inadequate nutrition is a problem throughout India, but the situation is considerably better in some states. Under-nutrition is most pronounced in Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan. Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu are characterised by high levels of wasting among children. Nutritional problems are the least evident in Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Goa, and Kerala. Even in these states, however, the levels of under-nutrition are unacceptably high.

Source: NFHS (National Family Health Survey) report

(Anosh Malekar is an independent journalist based in Pune)

http://www.infochangeindia.org/agenda6_03.jsp

InfoChange News & Features, October 2006

Labels:

PVCHR post in other than Hindi

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Featured Post

Tireless Service to Humanity

Dear Mr. Lenin Raghuvanshi, Congratulations, you have been featured on Deed Indeed's social platform. ...

-

http://www.blogger.com/post-create.g?blogID=17884293 पुलिसिया यातना की शिकार की ख़ुदबयानी समय Feb 02, 2011 | 5 टिप्पणियाँ लेनिन रघुवंशी मेरा...

-

जातिवाद , साम्प्रदायिक फासीवाद एवं नवउदारवाद के खिलाफ ' उत्पीडि़तों की एकता-नवदलित आन्दोलन ' में शामिल हों। भारतीय सामन्ती समाज ज...

-

Passion Vista and its partners profiled our Founder and Managing Trustee Shruti Nagvanshi as Women leaders look up to in 2023 https://ww...